In this reading, we’ll look at what I call the general web. Basically, the general web can be described as what your instructors mean when they say: “no internet.” (Note: some instructors include scholarly search engines in the “no internet” category – ask before using Google Scholar or PubMed.)

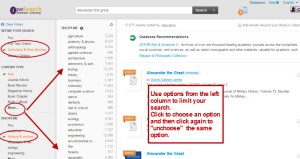

We’ve already looked at other web-based resources: these include library databases such as Academic Search Ultimate, plus many subject specific databases. You can think of library databases as specialized search engines. Library catalogs are another kind of specialized search engine. Our library catalog tells you what physical items the library owns: books, CDs, DVDs, etc. ) We’v also used OneSearch, the library’s new easy search system, which searches Stewart Library’s catalog, and most of its library databases from a Google-like interface. It also allows you to search materials from other libraries and universities.

In this reading, we’re going to look at the general web, focusing on how to find good information, how to give credit for the information you use, ways you can use Wikipedia, what to avoid and how to decide what to avoid.

Instructors say “no internet” because they know that the quality of information on the web varies wildly from excellent (rare) to horrible (common.) The easy way to avoid these issues with quality is to use a library databases or Google Scholar.

Instructors also know that it’s very easy to accidentally plagiarize when you use general web sources. If the source you use plagiarized, then you have plagiarized too. Sometimes the problem goes back several layers. For example: the original author plagiarized, either accidentally or on purpose. The next people to use that post are guilty of plagiarism even if they give credit properly and so are you because you are continuing the act of plagiarism. The fact that you did it accidentally may or may not help – it depends on your instructor.

However, the biggest issue with sources from the general web is figuring out what type of source you have. If you don’t know the type of source, you won’t be able to determine if it’s an acceptable for your assignment. Library catalogs, library databases, and (to some extent) scholarly search engines, identify the type of source and OneSearch lets you limit to a specific type of source. Outside of news sites, it’s rare for a general web source to clearly identify its type. You need to be able to distinguish a news article from a blog from a personal webpage from a term paper mill (Avoid the temptation to buy a research paper. You might not get caught buying the paper, but you will get nailed for plagiarizing.)

Despite all of these issues, there are still excellent sources available on the general web. The problem is a.) finding them, b.) figuring out what kind of source it is so you c.) can determine if it’s acceptable for your research and d. cite it properly.

There are several things you can do to increase your chances of finding good sources.

Make sure your instructor lets you use the general web to find sources before using them in an assignment.

- Do a good search

- Try typing in your research question first.

- If you’re not finding much or you have to go to the third page (or more) of results without finding much, try different combinations of keywords and key phrases. Keep a list of keywords and key phrases that work: you can often use them for library databases, too.

- Play around with keywords and key phrases until you have a search that finds the information you need . Because Google searches so many websites, the more specific you can be, the better. This is true for Bing and other search engines.

- Limit your search to the types of websites that are more likely to have high quality information by using a domain search. .Com, .tv, .edu are all domains. Country codes are the domains for a specific country (us = United States, uk = United Kingdom, mx = mexico, ru = Russian Federation.)

- Education (.edu) – especially sites associated with libraries and colleges. (The U.K. equivalent of .edu is .ac.uk, Australia: edu.au; Canada and Mexico usually just use country codes: .ca, .mx). CAUTION: be sure that you’re not using student work.

- Government (.gov, .mil, etc.) – These sites can be an excellent source of statistics and other primary sources.

- Organization (.org) – these include professional associations, foundations, special interest groups, museums, etc. Many of these groups provide high quality popular information on subjects such as controlling or living with specific medical conditions, information on requirements for a certain profession, etc.

- You can limit a search to a specific a domain several ways.

- Use the advanced search feature for the search engine you are using.

- For Google:

- Type in Google.com. Look at the bottom of the screen. On the far right, click on “Settings” Click on “Advanced Search.”

- If you don’t see “Settings” in the bottom right corner, look for the grid symbol in the top right corner. Click on it. Click on “Search,” you should then “Settings” in the bottom right corner. Click on it, then click on “Advanced Search.”

- Memorize/bookmark this link: https://www.google.com/advanced_search you can also just type: google.com/advanced_search

- For Bing: Bing no longer has an advanced search menu – you’ll need to use site: (see following)

- For Google:

- Type in your search followed by: site:edu (or site:org, site:gov, etc.).

- Example: searching using one domain name: Athena AND Apollo site:edu

- Example: searching using two domain names: Jupiter site:theoi.com (or wildcats site:weber.edu)

- Use the advanced search feature for the search engine you are using.

- Use a web page, do not use an entire website.

- Use entire websites only when you are studying website design or a similar subject where you look at the site as a whole.

- Make sure the web page has enough information.

- In general, a web page should have a least 300 words of continuous text on the same subject. Do a print preview. If you have close to a page of information, you should be okay.

- No tables of content, no paragraphs linking to a full article (use the full article,) no lists of links with (or without) brief descriptions.

- Look at scholarly sites for scholarly information.

- It’s usually easiest to use library article databases or scholarly search engines to find scholarly information; however, there are some good scholarly web sources.

- Sites such as those produced by libraries, museums and universities are frequently excellent.

- For example: http://dc.weber.edu/cdm/wars, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~1930s/front.html, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel01.html, and http://www.londonlives.org/

- Remember that education sites often include student papers. These are not considered scholarly sources. Look for online links to papers by professors. Papers by graduate students may be acceptable – check with your instructor to be sure.

- If you find a good student site that includes a reference list, check it for scholarly sources that might be useful.

- Look at popular sites for popular information.

- The great majority of general web sites are popular

- Look for high quality popular sites

- Reputable news sources such as CNN, the New York Times, the Salt Lake Tribune and the Deseret News, National Geographic is a good quality popular source. The Smithsonian has both scholarly (click on Researchers at the top right) and good quality popular sources – the scholarly sources are usually more focused and contain data. PBS and the BBC both have excellent information on many topics. Check out: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/ (we have the DVD), http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/vindolanda_01.shtml

- Associations, foundations, special interest groups and other organizations

- These sites often show bias.

- This is okay as long as you deal with that issue in your paper – in other words, you basically evaluate the site within your paper and explain why the information is valuable despite a clear bias.

- OR find a web site supporting the opposite view and compare and contrast the information found in each. For example: http://www.bradycampaign.org/ and https://home.nra.org/

- Some associations focus on providing useful information and raising money for research: http://www.cancer.org/

- These sites often show bias.

- Find primary sources

- The internet can be a great place to find good statistics, especially from government sources: http://bjs.gov/, http://www.healthypeople.gov/ . Many foreign governments have pages in English: http://www.insee.fr/en/, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/

- Adapted sources such as photographs of art objects, old newsreels, digitized letters and journals, original works and translations of authors. etc.

- For example: http://images.google.com/hosted/life, http://www.americanrhetoric.com/, http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/adaccess/, https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/project/art-project, http://www.lib.umich.edu/papyrology-collection/ancient-writing-materials-wax-tablets, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/trajan-column/article.html

- Remember, you need to use information from reputable websites.

- NOTE: while most primary source websites are free of advertising, there are some good ones, such as American Rhetoric, that use ads to pay for computer storage and the like. A librarian or your instructor can help you decide if websites with advertising have good primary sources. You can also google for reviews of the website.

- USE carefully: Tweets, blog posts, Facebook posts, user produced information such as iReport on CNN, personal YouTube videos, etc. Twitter can be used as a primary source that shows people’s reactions to a specific event, but not for much of anything else. You can also get this type of information from the comments section of online news organizations. Some blog posts, personal youtube videos, etc. can be good sources, but you will need to prove this to your instructor.

That leaves us with the big question – how do you tell what type of source you have?

- Determine the format of the source. This is often the easiest way to determine the type of source you’re looking at. For example:

- Most blogs have the word “blog” somewhere on the page. If not, check for blogging platforms such as Blogspot,Typepad and, of course, WordPress.

- The class blog doesn’t say blog because I bought a domain name (rememberwhereweparked.com) to make it easier to find.

- If you see a format like the class site – with entries and information in side columns – you very likely have a blog.

- The wiki format of Wikipedia is easy to spot – remember there are other wikis out there besides Wikipedia. One to check out is Wikimedia Commons, which has images, sounds and videos freely available. Most are public domain.

- If you see a number of short entries and a little blue bird, it’s probably a tweet. Other social media, such as Facebook, are usually easy to identify as well.

- Other formats, such as PowerPoint, videos, and PDF or Word documents have an obvious format, but the purpose is always not as obvious.

- Most blogs have the word “blog” somewhere on the page. If not, check for blogging platforms such as Blogspot,Typepad and, of course, WordPress.

USE COMMONSENSE! This is a big one. If you find a web page on your topic, but all you see is a summary in English, text in what appears to be cuneiform, and lines of dancing hamsters, this is not a good site to use for an academic assignment. Dancing hamsters are pretty much always a sign that you should avoid that web page when doing academic research – unless the web page is an academic paper discussing the phenomenon of dancing hamsters. (Don’t remember the Hamsters? Before there were cats, there were hamsters: http://pages.cs.wisdancingc.edu/~b oris/dance/ (note the .edu address.) Dance with music: http://www.hamsterdance.org/hamsterdance/ And check out the original source of the Hamster Dance music: Disney’s animated Robin Hood (1972): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_or3MKiU8Rw

Still not sure about the type of source?

- Avoid it.

- Desperately need the information on the page?

- Determine who produced the information (or source). This has two purposes:

- It will help you determine what type of source you have. For example: if the information is on the CNN page, you can assume that it is related to news in some way.

- It will help you evaluate the information. If you can’t find out who produced a source, or other pertinent information, you probably need to avoid it and ask for help to find the information you desperately need.

- Determine who produced the information (or source). This has two purposes:

- Determine what the aim or purpose of the source is.

- Information?

- Entertainment?

- Persuasion?

- Something else?

- This information will also help you evaluate the source, which in turn will help you decide if you can use it for academic research.

If you can’t figure out what the aim or purpose of a source is, you can’t find any information on who produced it, and you don’t know what type of source you have, avoid it. Ask a librarian to help you find the same information in a reputable source.