Subject Databases

Finding articles: background

To make finding articles easier:

- you need a good research question

- you need good keywords and/or key phrases

- you need to use your keywords and phrases to develop a good search statement. A search statement is just putting your keywords and key phrases together using AND, OR and NOT (see below)

- you need to search for articles in the right places

- you need to choose articles that are:

- directly relevant

- the right type of article (scholarly, popular, primary, etc.)

- good quality

In this reading, we’re going to look at using subject databases to find articles. In the next reading, we’ll look at using OneSearch and finish up in the third reading by looking at scholarly search engines such as Google Scholar & PubMed.

There are some basic terms you need to know to be able to find the best articles.

- Article: a written piece of non-fiction, complete in itself, found in periodicals, on the web and, sometimes in books. (adapted from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_(publishing))

- Periodical: a published work that appears in a new version on a regular schedule. The most common examples are journals, magazines and newspapers. Periodicals may available be in print, online or, for older ones, on microform. (adapted from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periodical)

- Journal: a periodical that contains scholarly articles. Most articles are peer reviewed (also known as refereed.) CAUTION: even scholarly journals contain material that is not scholarly, such as opinions, letters, editorials, book reviews, etc.

- Trade journals. The articles in trade journals are aimed at people in a specific field. Most articles are related to how work is done in that field.

- Magazine: a periodical whose content is aimed at a general audience. Most magazines are published weekly or monthly. Articles in magazines are popular or trade.

- Just to make life more confusing, there are a few magazines that contain scholarly articles. Science (US) and Nature (UK) are the most famous examples. These magazines, and a few others, that publish scholarly articles date back into the late 1800s when the terms were less defined. Unless told otherwise, assume a periodical is popular if it has “magazine” in its title.

- Newspapers: periodicals that are published daily and sometimes weekly (usually in smaller towns.) Their content is popular.

- News Reports: These are the video and online equivalent of newspaper articles. They may be written articles on a news site such as CNN, or they can be video reports from broadcast, cable/satellite or online sources such as ABC, CBS,NBC, & PBS among others. Treat them as you would a newspaper article. CAUTION: video reports can be good sources, but not all instructors accept them. Ask first!

- Newsletters are a subcategory of newspapers. They may be print or online.

- Much smaller – often just two or 3 regular size pages

- Usually monthly or quarterly (four times a year.)

- Often trade: Public Health Nursing Newsletter

- Can be popular: Berkeley Wellness Newsletter

- Instructors usually prefer a journal, magazine or newspaper article over a newsletter article.

CAUTION: magazines, newspapers and newsletters often report on studies of interest to their readers. These articles are NOT scholarly. How do you tell? The original study will be in a journal, it will have a section on methodology, and an extensive reference list. A report on the study in a popular periodical will often include who did the study and where they got the information. This is usually enough to help you find the original study. If you have problems, ask a librarian for help.

As usual, reports on historical topics are a bit trickier. Basically, if it’s in a magazine or newspaper or on the web, assume that you need to find the original article. As with more scientific topics, a good popular article will give you enough information to find the original.

Articles not in periodicals: these days you can find articles on the web that are not in periodicals. These include general web pages, blog posts, Wikipedia articles, etc. See the sections on web sources.

Library article databases: specialized search engines that search databases containing articles. Article databases can be general, covering many fields, for example: Academic Search Premier. They can also be very specific, covering one field or a group of related fields, for example: PsycInfo.

The articles in databases come from periodicals and occasionally books. Many are available in full-text. Full-text may be available from the database you’re searching, or you may need to click a link and find the full-text in a different database.

In a few cases, you may need to borrow the article on

interlibrary loan. Often, you can get an article in 24 – 48 hours (Monday – Friday). Often is not always. Do NOT count on all articles arriving in 24 – 48 hours, especially not during the last few weeks of the semester.

For additional definitions, see the Glossary of Library Terms on Canvas. On the course home page, look at the right menu near the center. Click on the link. Once you’re on the page, click on the PDF link to pull up the file.

NEVER, EVER PAY for an article. I repeat: NEVER, EVER PAY for an article. Check with the reference desk for ways to find it or get it for free or check the directions later in this set of readings.

Back to important definitions:

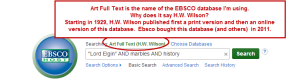

EBSCO/Ebscohost is NOT a database. EBSCO is a vendor (selling the databases), a publisher (putting the content on the web) and an aggregator (collecting content from different journals, magazines, etc.) EBSCOHost is the platform, or software, you use to access the information.

Proquest and Gale Cengage are two of the largest database vendors/publishers and aggregators after Ebsco.

- You must keep track of which database you are using:

- to make sure you don’t search the same database over and over

- because some citation styles require you to use the database name in the citation

- to make it easy for you to find again

The fastest way is to keep track of databases is to keep a list of the names you click on in the library’s list of databases. Keep a Word or Google Drive or Docs document or put all downloads from a database into a file labeled with a name such as ABI/Inform Global. However you do it, keep track. You’ll be happy you did once you start writing the paper.

Finding articles: search statements

A search statement is what you type in the find information. It can be as simple as one word, or as complex as several phrases combined using the boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT).

People usually find it easier to figure out search statements if they can see the steps, so check below for a step by step description of the process.

Finding articles: choosing a subject database

After you’ve come up with your keywords/phrases and a basic search statement, the next step is choosing the best subject database. Once you learn about OneSearch and Google Scholar (or maybe you already use them), you may wonder why you need to use subject databases. There are several reasons:

- They are often the best and fastest to place to find good articles on a topic

- You may be required to use them for upper level courses

- Often, your instructor will require you to use subject databases

How do you tell the best databases in your field?

- Do it the easy way: ask a librarian.

- Go to the library’s Article Databases page and find the subject closest to your topic.

- The top 3 databases are listed for each subject area

- Check the descriptions. If the top 3 don’t work, scroll down and read down the titles and descriptions until you find one that suits your topic.

Avoid these Ebscohost databases:

Use with care:

NOTE: most of the information in the above databases is also found in Academic Search Premier

SEE my list of suggested databases on Canvas. Go to the course home page. On the left side, click on “Pages” Click on the “all pages” button above the text, then click on the “Suggested Databases” link.

Tips for choosing the best database

- look at the requirements for your paper or project

- determine what kinds of sources you need: primary/second, popular/scholarly/trade. (Check out Information Types & Formats if you don’t remember what each is)

- Some databases, such as Academic Search Premier, have scholarly, popular & trade journals, magazines and newspapers. Academic Search Premier is a good database to begin with for most topics.

- Some databases, such as Sociological Abstracts, focus on one subject and have only (or mostly) scholarly articles.

- Some databases, such as Proquest Newsstand cover many subjects and have only popular and trade articles.

REMEMBER: As a rule, only newspaper and magazine articles are available for very current topics. It can take a year or more for a scholarly article to be published, even in a journal that’s only published online.

Finding Articles: searching subject databases

In this section, we’ll look at developing a good search statement. Remember that when you’re looking for articles you need a more specific search statement than you will when searching for books. There are a lot more articles than books and articles are about more specific topics than books. This means you can focus your search more than you can when looking for books.

Won’t a general search statement work for articles? Yes, if you want to wade through pages of articles and cross your fingers you’ll get lucky and find something on the first page. Using a good search statement will make it possible for you to find better articles without scrolling through pages of articles.

A focused topic with fewer but better sources is a lot easier to write than trying to figure out what to write about from a big pile of papers.

More is NOT better when it comes to searching for academic resources.

The bad news about search statements is that you may need to tweak or even rewrite your search statement to find the best articles.

I’m going to start with Academic Search Premier.

NOTE: I am using an older research question because it shows more clearly how you may need to play around with words and phrases and their order. Searching for information about people, such as Galla Placidia, is always easier because the one important term you’re looking for is a person’s name. Even name searching can be a problem, though, if the person used different names or spellings or you are dealing with names from a language such as Chinese, where there are several different ways of spelling the name in English..

Because most databases share similar structures, what you learn using Academic Search Premier as an example will transfer to other library subject databases. The trick is to avoid letting the superficial differences get in the way. Focusing on the similarities between databases will make it easier for you to learn how to use new databases on your own. OR, you can just ask a librarian for help. Remember, we have phone, text, chat and email, plus you can always stop by the reference desk and ask.

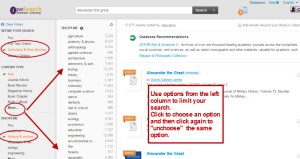

Most article databases begin with a basic search page. Usually, you will see a single search box that looks like Google. Like Google, library databases allow you to limit your search. Unlike Google, they have many more options. Dates, type of article, location, etc. are all things you can use to limit your search to the most useful articles.

If the basic search plus limits is not finding what you need, then look for a link that says Advanced Search. It will give you more options than you probably want. When using advanced search you need to read the directions or go the easy route and ask a librarian.

The research question I’m using for this reading is: Did Lord Elgin’s contemporaries consider his acquisition of the Parthenon marbles legal? The keywords/phrases I developed are: “Elgin Marbles,” controversy, acquisition, legality, contemporary.

First, you need to access the database. You can do this from home or on-campus. If you’re at home, the system will ask you for your Weber user name and password. This is your regular Weber user name and password that you use for the portal, Canvas, etc. NOTE: you may not be able to access databases from work – it depends on the security setup.

Pioneer: Utah’s Online Library

You can access Academic Search Premier and many other databases without signing in at: http://pioneer.utah.gov the new link is: http://onlinelibrary.utah.gov – both links are still working for now. . In the first column, click on: Alphabetical List and Information About All Databases (or follow this link.) If the name has either Restricted Access or Library Card Required, you will need a public library card to access – a few may be accessible only to K-12 students. Databases that don’t require a sign in are available only within the boundaries of the state of Utah. If you’re out of state, you will need to use Stewart Library’s databases. (If you’re interested, the databases that don’t require a sign-in use geolocation – you’re considered an acceptable patron as long as you stay in-state – the system recognizes Utah based internet addresses.)

Stewart Library has a large number of specialty databases that aren’t available via Pioneer, so you will need to use our databases as well.

You must access WSU databases through the library’s website to get access.

Go to: http://library.weber.edu. In the center column, click on the Academic Search Premier (ASP) link. If you are off-campus, you will be asked for a user name and password. This is your usual WSU username and password.

Let’s start with the basic search page. (Remember to click on the image to enlarge it.)

Ebsco Basic Search Screen

Courtesy EBSCO

Let’s focus just on the search box. Type in your search. Usually, you’ll need to use several terms. Not sure whether to use AND or not? Try the search without AND. If you find what you want, great. If not, search again, using AND. Remember to indicate key phrases by enclosing them in quotation marks.

So, for my research question: Did Lord Elgin’s contemporaries consider his acquisition of the Parthenon marbles legal? I need to start with a specific search statement. Remember, you need to be specific when you search for articles. So, I might start with something like:

Ebsco Basic Search Screen – this one is Academic Search Premier

Courtesy of Ebsco

And, I’ll get something like this:

Academic Search Premier – no results

Courtesy of Ebsco

Most people’s immediate reaction is to broaden the search. I probably do have too many keywords/phrases. However, I also need to change my keywords/phrases. Usually, when you don’t find anything, you need to keywords and not use as many . Occasionally, you will need to change databases. For this topic, I might want to try an art database.

Not sure what the Parthenon Marbles (AKA Elgin Marbles) are? Check out the Wikipedia article.

Now it’s time to start playing around with terms, boolean connectors (AND, OR, NOT) and with the number of keywords/phrases.

- I start by dropping “acquisition” and “controversy” since those terms are understood for this subject. (this technique does not work for all subjects)

- Next, I try replacing some of my terms. I try: “Elgin Marbles” AND history AND legality.

- Keywords like “contemporary” don’t work unless you’re looking for something like “contemporary art.”

- “History” gets at the idea that I want to find information on Lord Elgin’s time.

- I find one article, but it’s about the current debate over repatriation of the marbles and it doesn’t discuss the views of people in Lord Elgin’s time.

- I try “Elgin Marbles” AND history AND controversy

- I find another article, but it’s about the current debate, too.

- It mentions the fact that Lord Elgin’ contemporaries felt what he had done was illegal, but on sentence is not enough. As a rule, you need several on-topic paragraphs before you can claim an article is a source.

- Since the marbles are controversial and the previous article mentions people at the time felt what he did was illegal, I drop controversy and type in: “Lord Elgin” AND marbles AND history.

- I find several articles and a couple of them have information. The articles are relevant, but don’t provide much information.

- NOTE: I might have decided that my problem was the fact that I didn’t know if it was better to use “legality” or “legal.” You can search for both terms in two different ways.

- Use OR. Remember to put parentheses around the terms connected with OR. So: (legal OR legality)

- Another way is to use truncation.

- The * symbol (shift-8 on the keyboard) will find different endings starting from the letter before the *. So, if I type legal*, the system would find: legal, legality. Histor* would find history, historical, historian.

- Be careful not to truncate too much. Rat* finds rat, rats, ratio, rational, rationale, rating, ratings, etc. This is too general to be useful. In fact, you will just make work for yourself.

- The asterisk (*) is a wildcard. When you use a wildcard to find different endings, you are using truncation.

- NOTE: Most search engines do not allow truncation or wildcards. They do something called stemming, which produces results similar to truncation. If stemming doesn’t help, then combine the terms with OR – remember to put parentheses around the terms connected with OR.

At this point, I need to switch to a subject specific database such as Art Fulltext. Art Fulltext looks like Academic Search Premier, but covers more art journals and doesn’t cover general magazines and newspapers. I’m going to use the search that worked best in Academic Search Premier.

Basic search screen for Art Fulltext (Ebsco.)

Courtesy of Ebsco.

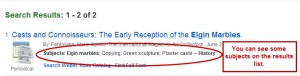

This search finds two articles. The first one looks really good until I read the abstract. It may have a little bit of information, but not a lot.

How to read the Art Fulltext result screen.

Courtesy of Ebsco.

I try a couple of other searches – “Lord Elgin AND history AND marbles is the first search. The second search is “Lord Elgin AND legal* (note the use of truncation.) I decided that I didn’t need to use “marbles” as a term because article in an art database would most likely be about the Elgin Marbles.

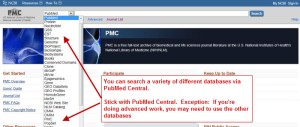

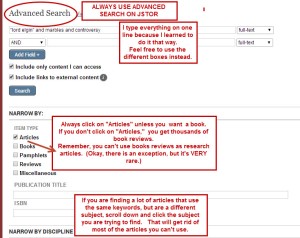

I found about 10 more articles, but none of them were really relevant. At this point, I decide to use a database that covers history and art – JSTOR. JSTOR stands for Journal Storage. JSTOR was created to make sure that the online versions of older journals (and a few magazines) were kept. In the beginning, JSTOR had only the older articles. Now there are some current articles, plus some books. (NOTE: we do not have access to the books or the current articles.)

However, most of the JSTOR database still consists of articles that are at least 3-5 years old. The majority of these articles are available in fulltext. Because of the subjects that it covers, JSTOR can be a very good place to look for articles in history and art. However, because you are missing the most recent 3-5 years, you must check another database for more current information. If you don’t check for more current articles, you could miss a critically important paper.

Never use JSTOR alone. Always check a different article database for more current information.

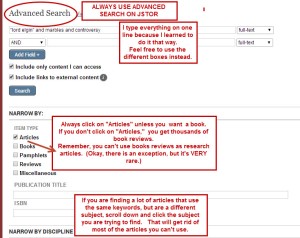

Doing a search on JSTOR.

Courtesy of JSTOR.

ALWAYS USE ADVANCED SEARCH ON JSTOR. ALWAYS! (Unless you like doing extra work.)

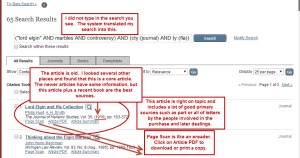

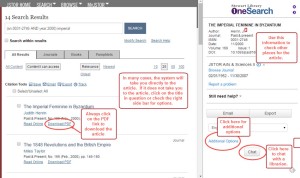

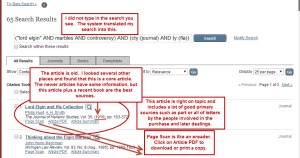

JSTOR results page.

Courtesy of JSTOR.

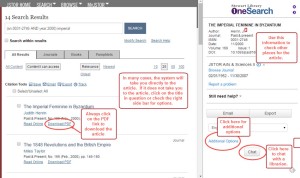

This time, I found 65 sources and some of them are relevant to my topic. However, a lot of the sources have nothing to do with my topic. If I only needed two or three articles, I’d probably browse through until I found a couple that would work.

If you need more than two or three articles, there are several things you can do. The easiest way to find more sources is to look at the record for one of the relevant sources, see what subject and/or title terms they used and try some of them. If you’ve tried several different searches and still don’t find anything, you probably need to switch to a different database or do it the easy way and ask a librarian for ideas.

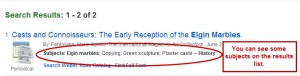

Sometimes you can get a list of subject headings from the results list. (Note: for JSTOR, you need to look at the article title and the abstract or article summary if there is one.)

Finding keywords on the results screen.

Courtesy of Ebsco.

Other times, you need to look at the complete record. Click on the article title to pull up the record. (On Ebsco databases, you can also mouse over the page icon with the magnifying glass on the right of the title.)

Finding keywords on a full record.

Courtesy of Ebsco.

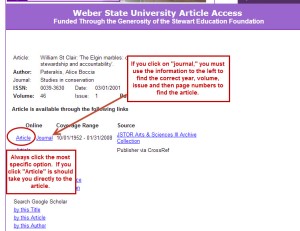

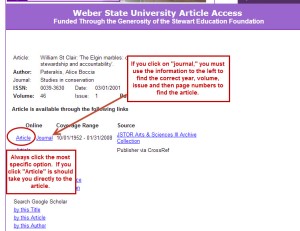

Avoid the temptation to limit to full text. Limiting to full text could result in you missing the perfect article. When you click on the Find Fulltext link, the system will either take you directly to the article, or it takes you to an article access page that links you to the full text of the journal in a different database. The page used to look like:

Using the Article Linker to find full text in a different database.

Courtesy of Ebsco.

If the system finds a link, it looks like this.

This is what Article Access looks like if it finds a link.

Courtesy of JSTOR & Proquest

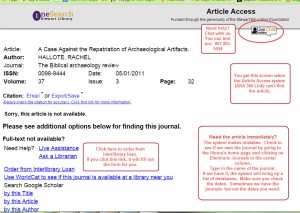

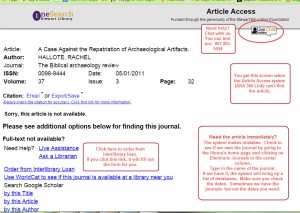

If the system doesn’t find a link, it looks like:

This is what the article access page looks like if it does NOT find a link.

Courtesy of Proquest

Click on the article link to see the article. (If all you see is a journal link, you will need to click on journal then look up the correct year, volume, etc.)

NOTE: Occasionally, you’ll run into a topic where we don’t seem to have any fulltext. That happened to me with this topic. I had to go to the second page to find an example. If you can’t find full text for an article you want, ask a librarian to show you how to use interlibrary loan – we can usually get an article for you (electronically, from another library) in 24-48 hours. During the last few weeks of school, expect interlibrary loan to take longer.

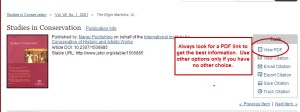

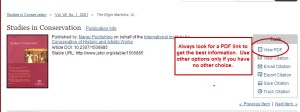

Once you find the article in another database, you need to find the PDF of the article. Always click on the PDF to make sure you get any charts, graphics, images, etc. You may have to search for the PDF link. Usually, it’s somewhere near the start of the article. However, it can be at the top right or left of the page, right about the article text, under a picture of the issue, buried in the citation information, etc. Having trouble? Ask for help.

Always try to find the PDF of your article.

Courtesy of JSTOR

Need more articles? If you found a lot on Academic Search Premier, you can use them or you can redo your search using different keywords. However, you might find better articles by changing to a subject specific database. As was the case with my topic, I had to try a couple of different subject specific databases. (Welcome to the wonderful world of historical research.)

Remember – library article databases may look different, but with the exception of specialty databases (for example: accounting), they are structured the same. You just need to look around, figure out what’s going on and then start to search. As always, you can go the easy route and ask a librarian for help.