The purpose of this course is, again, to make it easier for you to find the kinds of information your instructors are asking for. While articles and web pages are fairly easy for most people to find, books are another story. Since this is an online course, I don’t believe it’s fair to ask people to come to the library to get a book.

So, I’ve chosen to show you how to decide if a book is worth reading when all the information you have is what you can find online.

If you can evaluate a book with nothing but the information you can find online, doing so with an actual book in your hands (or on your phone, tablet, etc.) should be easy.

FINDING BOOKS

Libraries contain all kinds of sources, including books, ebooks, CDs, DVDs, games, etc. How do you find them? There are several ways:

- Use the catalog of a specific library, such as WSU’s Stewart Library – this is the easy way to begin. Stewart Library’s catalog contains print books and a few online books.

- Don’t see what you’re looking for there? Check out our eBooks page. We have over 140,000 books on Ebsco eBooks alone. Most of the library’s ebooks must be read on your computer: Ebsco eBooks is the only place you can download ebooks to a tablet, ereader, or phone as well as a computer.

- Then, if you can’t find what you’re looking for, try Worldcat.

- Worldcat is a catalog of all the books from most U.S. libraries and some international libraries. There is a free version, but it’s best to use our subscription version because you get a lot more information and it does things like fill out interlibrary loan forms for you. You must use the subscription version to answer any assignment questions.

- You can use Google Scholar. One of the advantages of using Google Scholar is the cited by feature. When you click on the cited by link, it provides a list of other sources that cite the first source in their bibliography or reference list. This is an easy way to find other sources on your topic.

- You can use Google Books. This is a good way to find free online books. The catch here is most free books are dated 1923 or earlier because of copyright law. You will find later books listed, but will still have to use the catalog or Worldcat to look them up, so you might as well start with the catalog or Worldcat. Occasionally, you can find a more recent book that allows you to look at a number of excerpts. A few will give you 60 pages or more.

Avoid the temptation to use these excerpts as sources because:

-

- It’s considered cheating to pull pieces from a book that’s only partially available on Google Books (or any other site). While you don’t always need to read an entire book, you should have the whole book available.

- If you don’t have the whole book available, you may completely miss the author’s point

- Before using a book as a source for a paper or research project, you need to have any appendices, the index and any back matter (see below) to evaluate the book properly.

- It’s considered cheating to pull pieces from a book that’s only partially available on Google Books (or any other site). While you don’t always need to read an entire book, you should have the whole book available.

- You can use the Internet Archive. The Internet Archive is working to archive, or store, all kinds of online information. This includes ebooks, both pre-1923 as well as some newer ones, video, audio, web pages, etc. Click the menu links at the top of the page to access a specific search page for each type of source. You can also use Project Gutenberg, which was the first online library of free books (it predates Google by years); however, I believe most people will find the Internet Archive easier to use.

-

- Just for fun: have the URL for a web page that no longer works? Put it into the Wayback Machine and see if you can find a copy. Click on blue highlighted dates to see snapshots. (NOTE: some sites have removed their information from the Archive.)

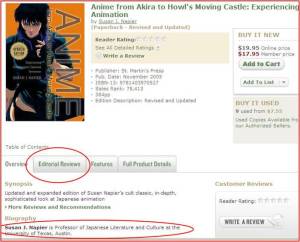

- You can use Amazon to find a recent book on your topic, but Amazon may not list older, possibly useful, books on your topic AND you will still have to use a catalog to find them, unless you want to buy the book. If you’re not sure of the title of a book, CD or DVD, Amazon is a good place to check.

- You can do a Google or Bing, etc., search and hope a book comes up.

- This is usually a good way to waste a lot of time.

CATALOGS

We’re going to look at catalogs in this reading. A catalog lists what a library owns physically, for example: print books, CDs, DVDs, etc. It also lists what a library owns access to such as online journals, ebooks, streaming music, and streaming video. Our library catalog is available via the Stewart Library website. To access it, click on the yellow book icon, then click on the advance search link underneath the search box. You do not need to login to use it. As I said above, it contains only print books and a few links to online books that haven’t been removed yet.

NOTE: we’ve recently subscribed to the academic collection from Ebsco ebooks. Our Ebsco eBooks contains about 140,000 ebooks on all topics. You can download them to your computer, phone, tablet or ebook reader. To find these books, go to the library’s home page: http://library.weber.edu. In the center column, click on eBooks Ebsco eBooks shows up a number of different places on the eBooks page.

One very important characteristic of a catalog is that it contains large chunks of information: Whole books, complete DVDs, entire CDs. This means that when you search a catalog, you will often need to use broader, or fewer, keywords & key phrases. You may also need to use different keywords than you will use searching for articles or websites.

When I say broader keywords, I do not mea using one or two unfocused keywords, but rather focusing on the core of your research question and not the details.

For example: I’m interested in Alexander the Great and why he decided to conquer the world. I try searching for “Alexander the Great’ AND “world conquest” AND reasons. After trying a number of searches, “Alexander the Great”and empire found the best books.

In order to search a library catalog successfully, you need to use boolean and phrase searching.

A quick refresher:

- AND search (= all of the words) – an AND search tells the computer to find sources where all of the words you type in appear – this is the default search on Google and many library databases. Not sure if you need to add in AND? Try the search without AND; if you don’t find much, then add the AND between keywords.

- OR search (= any of the words) – an OR search tells the computer to find sources where at least one of the words you typed appears. Some OR search are actually “any of the words” and “all of the words” searches. The easiest way to see what they’re finding is to look at your search results. If you have at least 2 search terms appear in one result, then you have an “any or all of the words” search.

- Always use a capital OR. You must capitalize OR when using Google and many library databases, so it’s best just to get into the habit of typing OR.

- IMPORTANT NOTE: if you combine two or more words with OR, be sure to put parentheses around the words. For example: (adolescent OR teen). If you leave the parentheses off, you will get weird (and bad) results.

- NOT search (= missing the word/words that appear after NOT) a NOT search is very tricky to use. You can lose good sources when you use a NOT search.

- For example: you need articles on teaching French. For some reason you are getting a lot of articles on teaching Spanish. You type the search French NOT Spanish. You miss the perfect source because it’s on teaching both French and Spanish. (If you are getting a whole lot of articles, then go ahead and use NOT.)

- Phrase search (= search for ALL the words inside quotation marks, include “the,” “of,” and other little words). This can be a really useful search, but you need to be sure to use good phrases. “Cultural heritage” is a good phrase because you expect to see those words together in that order. “The destruction of cultural heritage” is not a good phrase because you didn’t use words that people expect to be together.

- One way to judge a phrase is to search for a book or an article. If you only find a few books, then the phrase is probably not a good one. Take the separate words (and sometime phrases) and combine them using AND.

- For example: use destruction AND “cultural heritage” instead of “The destruction of cultural heritage”

- One way to judge a phrase is to search for a book or an article. If you only find a few books, then the phrase is probably not a good one. Take the separate words (and sometime phrases) and combine them using AND.

Do you have to capitalize AND, OR, & NOT? More and more library databases and other search engines are requiring you to capitalize, so you might well get into the habit. Right about now, you’re probably asking why you have to use boolean and thinking you can find sources without it (the technical term for searching without boolean or phrases is natural language searching). That may be true a lot of the time. You have to know boolean because:

- You need to know how to do boolean searching for the times when natural language searching doesn’t find anything

- Even when natural language searching works, you can use boolean techniques to save yourself from having to wade through thousands of sources.

- You have to know how to use boolean searching to pass the last assignments.

You may also be thinking, why bother to use a library catalog or subscription Worldcat. There are a couple of reasons:

- Information in library databases, including subscription Worldcat, is much more structured than information just out on the web. Structured information makes it possible for you to search in many different ways such as: keyword, subject, author, publisher and more. It also allows you to limit the sources that are found by date, format, location, etc.

- Because the data is structured, if you use a good search, you will find the sources you need much more quickly then you can when using Google Books, etc.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Now you know where to search and how to search, you’re ready to try it in the real world. I’ll continue to use the Elgin Marbles question because it provides a better example.

My research question is: Did Lord Elgin’s contemporaries consider his acquisition of the Parthenon marbles legal? The keywords/phrases I developed are: “Elgin Marbles,” controversy, acquisition, legality, contemporary.

My alternative keywords are: ”Parthenon marbles,” debate, “nineteenth century.”

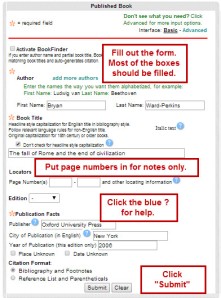

The first examples are from the Stewart Library catalog, because that’s the one you will be using the most. See the assignment example for how to search Worldcat.

- I always start by typing all of my keywords/phrases in the general keyword box, just in case I get lucky. Since catalogs have big chunks of information, typing in all my main keywords/phrases will probably be too focused.

- As I suspected, my keywords were too focused. Next, I’m going to try searching the most important keywords/phrases, which are “Elgin Marbles” and controversy.

- I could have tried contemporary instead of controversy, because Lord Elgin’s purchase of the marbles was controversial to many of the people of his time, but I used controversy because sources about the controversy usually give the history of the controversy. Using contemporary might just find what’s going on now. (I don’t need to type AND because I know most library catalogs and databases assume you want AND between each word.)

- “Elgin marbles” controversy doesn’t find anything. Neither does “Elgin marbles” contemporary. I tried using “Parthenon Marbles” instead of “Elgin Marbles. No luck. I try “Elgin marbles.”

When I search, I find one source. (Typing in “Parthenon Marbles” produces the same book.) Since I only find one, the system takes me to a screen with information about the book (it is a book.) This information is called a record. Catalog records include information about the title, the author, the year of publication and for newer books, content notes. They also list special formats, such as CDs, DVDs, etc. At the bottom of the page, there is information on which library has the book (we have a small library on the Davis campus), the collection and the call number. You need this information to find the book in either library.

I notice the date of the book is 1960. Even for earlier periods of history, it’s better to start with newer books. New information is discovered all the time, even in ancient history. I decide to do another search. I know that the Elgin Marbles are from a Greek temple called the Parthenon. I also know (and you could ask someone) that most recent books on the Parthenon include a section of the Elgin Marbles controversy. I get the list below.

- I know (because I order books in this area) that the first book would probably have something. Unfortunately, it hasn’t arrived yet. (NOTE: in real life, you can use Interlibrary Loan and we will borrow the book for you from another library.)

- The second book, which I ordered (and also own a personal copy of) is a funny, but accurate, fake travel guide to ancient Athens. It will not have the information I need. How do you tell the book isn’t serious if you haven’t read it? One big clue is the cover – serious books do not show ancient statues with modern luggage.

- The third option is a videorecording, specifically, a DVD. The record tells me it’s a PBS video, so it’s probably decent quality. The notes tell me that it talks about the Elgin Marbles. I decide that the DVD will work. NOTE: For this class, you may use a DVD or VHS on your topic instead of a book. Always clear using a video with your instructor. Many will not qallowvideos as sources.

- If my instructor didn’t allow me to use videos, I could click on the subject heading links to try to find more books. In this case, there is one other approach I could take.

- Instead of looking for books on the Elgin Marbles, I could look for a book on Lord Elgin. Lord Elgin is a title. To find books about him, I need to know the rest of his name, which is Thomas Bruce. I would actually search for him under the keywords: Elgin, Thomas Bruce.

- NOTE: be careful when searching for people who are usually known by a title. Library catalogs and databases have very specific ways of formatting names. You may need to play around to find the right combination.

Example: Queen Elizabeth I or St. Barbara are in the catalog as: Elizabeth I, Queen of England and Barbara, Saint.

- In some cases, we simply don’t have a book on a subject (try combinations of your keywords or different keywords before giving up. You can ask a librarian for help too.)

- If we don’t have a book, you will need to either use Worldcat, Google Books, etc. to find more books and borrow them using Interlibrary Loan OR use more articles instead of books.

- NOTE: you could also check out what the U, USU and BYU have. Your Weber Wildcard can be used to check out books at other Utah universities.

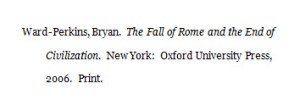

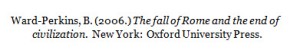

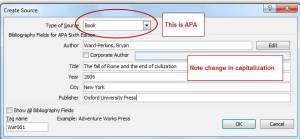

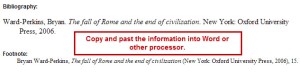

- Do it the easy way: using the bibliography of a Wikipedia article to find sources is one of the valid academic uses of Wikipedia. Make sure the book you choose is fairly new. Choose older books only if they are primary sources or otherwise valuable (ask your instructor or a librarian). The bibliography/reference list is also one way to judge the quality of a Wikipedia article. Good articles have good bibliographies or reference lists. I looked at the reference list and found:

- I know it’s a book, because it has a publisher, Oxford University Press. A journal article would have an article title, journal name plus volume and page numbers.

- I look at the description on Amazon and check out the table of contents, etc. and the book looks perfect. The fact that it’s published by a university press means it’s probably good quality.

- I fill out the interlibrary loan form, get the book in about 5-7 working days, read the part that interests me. (I also scan it and the information I need for evaluation so I have a copy if I need it) and use it for my paper. (If you start with Wikipedia, check our library catalog before using interlibrary loan – we might have it.